Story time.

When I was writing for Star Wars: The Old Republic, BioWare Edmonton’s design director called me into his office and said “How do you feel about working on Mass Effect 2?”

My response was, “Um… why, do they need me?”

ME2 had six writers on it already. But it turned out that three of them were leaving the company when they were done writing the dialogue, and a fourth one broke his shoulder slipping on an ice rink at a kid’s birthday party. The grunt-work writing remained: the Codex entries, the Galaxy Map, the weapon descriptions — essential words to make the game function, but nothing as glamorous as writing characters the audience would love.

So I took over the non-voiced text from the previous IP expert, Chris L’Etoile, starting with the Galaxy Map. I said, “This works like Star Wars, right? Ice planet, swamp planet, city planet?”

In response, Chris sent me a chart of the minimum molecular weights of gases retained by a heavenly body. This was important to get right, he said, because 90% of the 300 planets on the map were not going to be able to support life. They were going to be barren rocks with gases, just like in the actual Milky Way. My job was to turn them into something interesting and accurate at the same time.

“Uh… does your audience actually care about this?” I asked.

“Yes,” Chris replied. “This chart is why you can’t terraform the Moon. Even if you pumped in all the oxygen and nitrogen you needed to create an atmosphere, the weak gravity means it’d float off into space. You need to know that, because this is the way we did it on Mass Effect 1 and some of our fans on the forums are astronomers. They’ll know if something is off and they’ll tell everyone. By the way, remember that BioWare’s CEOs are doctors, so they’ll know if any alien biology doesn’t work. Good luck!”

That was my introduction to writing hard science fiction, or at least harder than I’ve seen in any other space opera video game. Video games, as a rule, are soft science fiction, with plasma guns and teleportation and all kinds of tech that would require huge leaps in science but makes for easy narrative grease.

I had to learn the rules before I broke them, so I learned all I could about planetary formation and the early stages of life on Earth. Then we got to the Codex entries on weapons, and I had to figure out how to make things sound awesome and match up with what the combat team wanted. I did this through the game shipping and 9 pieces of downloadable content. I also headed up the team on the Cerberus Daily News, 365 player-facing entries that had to be important enough to seem newsworthy but inconsequential enough that we didn’t complicate the writing of Mass Effect 3.

By the time Mass Effect 3 rolled around, I was designated as “the writer who cares about the science,” and was dubbed the de facto IP expert. I did what I could to make the game and its accompanying DLC (another 9 pieces) as consistent with the laws of physics as possible.

Below are some examples I’m proud of.

The Thanix “Cannon“

The Thanix weapon you get for your crew’s spaceship is an example of the writing “iceberg” in ME2: a lot of effort, 90% of which the player will never see. We knew that we wanted the weapon to be adopted from Sovereign’s main gun in Mass Effect 1, and that it was super-advanced. The Reapers had a civilization millions of years old and technology that should sound awesome.

It couldn’t just be a laser, because how boring would that be? Further, it shouldn’t be a particle beam (you get that as a hand-held weapon in the game), or a microwave/maser weapon, or anything we’d heard of before. On the other hand, it still had to make physical sense and look like a directed-energy weapon, because that’s what the cutscenes in ME1 showed. So the bar was high.

I ended up scouring pages from the U.S.’s Defense Advanced Research Project Agency and ultimately a 1951 book by Arthur C. Clarke from which a DARPA project (MAHEM) was inspired. Yes, it was an old idea… but if an old idea is grounded in physics, it still works.

Palaven, the Turian Homeworld

I like this one because it’s an example of literal world-building. It’s also an example of where the Codex and Galaxy Map overlapped, and I had to say similar-but-not-identical content in two places.

We met turians in Mass Effect 1, and Chris L’Etoile’s codex entry mentioned that their homeworld had intense solar radiation, more so than Earth. This is why turians look metallic — their life evolved to incorporate metals in their organic processes so that their silver carapaces reflect away the damaging rays.

But when we finally got to go into the system in Mass Effect 3, I had a conundrum. How would their plants work? Turians breathe nitrogen and oxygen just like humans, and their plants photosynthesize the same… so if the plants were metallic, wouldn’t they be handicapping their energy source?

That’s when I researched my butt off, and found out how Earth’s life deals with intense solar radiation. I wrote that bit about shutting down metabolic processes during the day and repairing the damage at night because lichens on Earth do that already. That’s how good science fiction works — you find a factual core around which you can wrap a narrative.

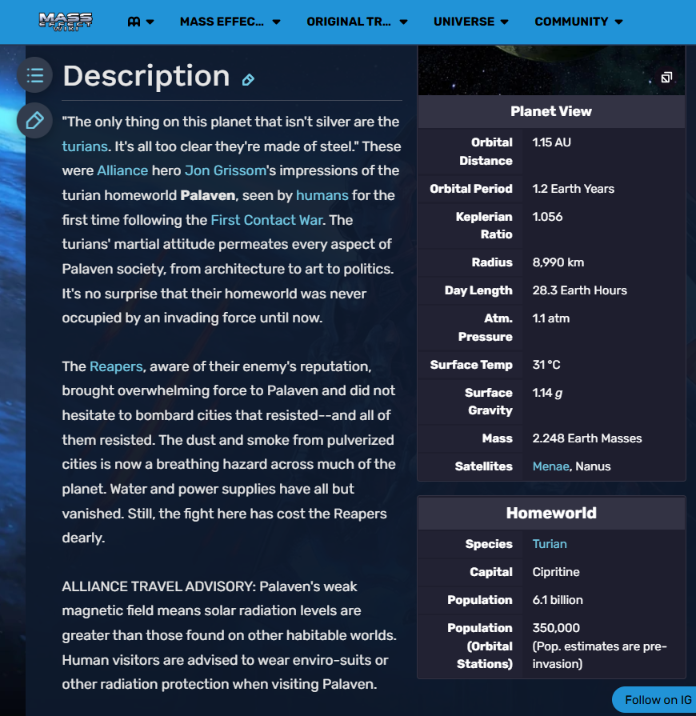

The Geth Plasma Shotgun

I bring this one up in interviews a lot because it’s an example of being a team player. The combat designers wanted an “unshotgun” that could operate at longer ranges and charge up for higher damage. They spent a lot of time and some art resources on it and they had really good gameplay reasons: certain classes that could use shotguns were due for a buff and would love this weapon. It was the “energy shotgun,” or the geth’s “Plasma Shotgun,” since ME1 mentioned that geth sometimes plasma-burned Alliance soldiers.

Here’s the thing: plasma weapons, in physics terms… are bullshit.

I know they’re in a lot of science fiction, but there are reasons real-life weapons manufacturers aren’t making them. You don’t fire “bolts of plasma” and certainly not “shotgun shells of plasma.” Plasma’s a superheated gas. A stiff wind would blow it back in your face. Nor is it easy to magnetize it and fling it, especially with enough force to do much to an armored, moving opponent. It’s orders of magnitude easier to make a gun or flamethrower that does the job better and cheaper.

But… my job is not to make other people throw out their work. So I didn’t say no, and I didn’t give up. Giving up is not in my workflow.

I talked with a physics teacher I once had who now works at NASA, and with a science-fiction conflict-simulations group, and we brainstormed over e-mail. The result is what you see up there: room-temperature superconductors, miniaturized into toroid-shaped shotgun rounds, that are charged up and flung at the enemy, flash-creating plasma on impact. Pow. The Geth Plasma Shotgun that made the writing, art, and combat teams happy. And players got that sweet gameplay we all wanted. They freakin’ loved it.

Asteria

This was a little throwaway entry in the Galaxy Map. I wanted to include it because every science fiction property in the world has habitable planets that are filmed on a back lot in Southern California or something similar. The air is hardly ever a problem, the animals look like pets from a store like those snakes in the Dagobah swamps… they’re just not alien.

So, I made Asteria, which is a habitable garden world… except the numbers are 95% right instead of 100% right. It’s just a little off-target, with too much CO2. Not enough to totally prevent humans from adapting, but retaining enough heat to feel worse than Earth. And advising visitors to, almost literally, bring a canary like it’s a frickin’ coal mine.

This detail was possible because the player can’t land on Asteria, so we didn’t have to expend resources on some weird mechanic showing it off. You don’t want to go there? Super. We give you just what you want, and get text that evokes versimilitude to the universe at the same time.

Bekenstein

I wrote this one up for the Kasumi: Stealing Memory DLC, the planet where Kasumi Goto takes you to an arms dealer’s fancy party. Having seen farming colonies like Eden Prime in Mass Effect 1, I thought it’d be neat to make the planet the equivalent of the humans’ New York or Tokyo. Its proximity to the Citadel made it all come together.

My one regret is that if you’re not from the USA, “more expensive than surgery” may not ring quite as true.

The Omni-Blade

This was an example of retroactive continuity and avoiding worse retroactive continuity.

By Mass Effect 3, we wanted a melee attack that was cooler and more unique than Shepard elbowing his enemy. Word came down from on high to make a “holographic switchblade.” Which, of course, doesn’t make sense. Early ideas (from someone I’d rather not rat out, since God knows I’ve had my share of non-starters) justified it as saying it was a form of “hard light.”

Of course, the previous two games didn’t have any hard light. No lightsabers, no holo-shields. And this wasn’t even newly-captured Reaper tech, it was a weapon Shepard has from the get-go. It was going to have variations based on Shepard’s character class, so the Alliance had clearly mastered it.

So, it was up to me to craft a Codex entry explaining what this glowing blade (or bludgeon, or whatever) actually was. And, as a bonus, I avoided saying they were just invented, because at the time we didn’t know if we were going to visit the First Contact War in another game or comic or whatever else the franchise needed next.

Thus, this entry: highlighting that Alliance soldiers, like real-life modern soldiers, rarely kill in hand-to-hand, but the Reaper invasion demanded new tactics.

And Let’s Not Forget the Cerberus Daily News

President Huerta’s Predicament

I wanted to have some news items from Earth, since ME1 and ME2 never took us there, and many players would want to hear what Earth life is like. Some of my biggest writing influences were in the cyberpunk genre, and though Mass Effect is more space opera than cyberpunk, the advancements of technology would change the world.

The Huerta stories explored this idea — that humans would use data storage in medicine, and somewhere, the law would need to draw the line differently regarding what “death” really is. Of course, the story grabs more attention if you give it enormous stakes, such as the Presidential line of succession. Incidentally, the Huerta stories showed up as a tiny mention in Mass Effect 3 with Huerta Memorial Hospital — a hospital named after a President who insisted he wasn’t dead yet. Welcome to the politics of the future.

Let’s end this sample with a bang — the final entry of the Cerberus Daily News when the collected peoples of the galaxy started to figure out that the Reapers were coming. This last entry left on an ominous note (if you were following the storyline ending in ME2 and/or the Arrival DLC) and the next thing the players would see was ME3 trailers that showed the Reapers attacking Earth. I thought this put a nice capstone on the entries and built the hype like we needed to.